How the Great Firewall of China Detects and Blocks Fully Encrypted Traffic

Abstract

One of the cornerstones in censorship circumvention is fully encrypted protocols, which encrypt every byte of the payload in an attempt to “look like nothing”. In early November 2021, the Great Firewall of China (GFW) deployed a new censorship technique that passively detects—and subsequently blocks—fully encrypted traffic in real time. The GFW’s new censorship capability affects a large set of popular censorship circumvention protocols, including but not limited to Shadowsocks, VMess, and Obfs4. Although China had long actively probed such protocols, this was the first report of purely passive detection, leading the anti-censorship community to ask how detection was possible.

In this paper, we measure and characterize the GFW’s new system for censoring fully encrypted traffic. We find that, instead of directly defining what fully encrypted traffic is, the censor applies crude but efficient heuristics to exempt traffic that is unlikely to be fully encrypted traffic; it then blocks the remaining non-exempted traffic. These heuristics are based on the fingerprints of common protocols, the fraction of set bits, and the number, fraction, and position of printable ASCII characters. Our Internet scans reveal what traffic and which IP addresses the GFW inspects. We simulate the inferred GFW’s detection algorithm on live traffic at a university network tap to evaluate its comprehensiveness and false positives. We show evidence that the rules we inferred have good coverage of what the GFW actually uses. We estimate that, if applied broadly, it could potentially block about 0.6% of normal Internet traffic as collateral damage.

Our understanding of the GFW’s new censorship mechanism helps us derive several practical circumvention strategies. We responsibly disclosed our findings and suggestions to the developers of different anti-censorship tools, helping millions of users successfully evade this new form of blocking.

1 Introduction

Fully encrypted circumvention protocols are a cornerstone of censorship circumvention solutions. Whereas protocols like TLS begin with a handshake that comprises plaintext bytes, fully encrypted (randomized) protocols—such as VMess [23], Shadowsocks [22], and Obfs4 [7]—are designed such that every byte in the connection is functionally indistinguishable from random. The idea behind these “looks like nothing” protocols is that they should be difficult for censors to fingerprint and therefore costly to block.

On November 6, 2021, Internet users in China reported blockings of their Shadowsocks and VMess servers [10]. On November 8, an Outline [42] developer reported a sudden drop in use from China [69]. The start of this blocking coincided with the sixth plenary session of the 19th Chinese communist party central committee [4, 1], which was held on November 8–11, 2021. Blocking these circumvention tools represents a new capability in China’s Great Firewall (GFW). To our knowledge, although China has been using passive traffic analysis and active probing together to identify Shadowsocks servers since May 2019 [5], it is the first time the censor has been able to block fully encrypted proxies en masse in real time, completely based on passive traffic analysis. The importance of fully encrypted protocols to the entire anti-censorship ecosystem and the mysterious behaviors of the GFW motivate us to explore and understand the underlying mechanisms of detection and blocking.

In this work, we measure and characterize the GFW’s new system for passively detecting and censoring fully encrypted traffic. We find that, instead of directly defining what fully encrypted traffic is, the censor applies at least five sets of crude but efficient heuristics to exempt traffic that is unlikely to be fully encrypted traffic; it then blocks the remaining non-exempted traffic. These exemption rules are based on common protocol fingerprints, a crude entropy test using the fraction of set bits, and the fraction, position, and maximum contiguous count of ASCII characters in the first TCP payload.

Due to the black-box nature of the GFW, our inferred rules may not be exhaustive; however, we evaluate our inferred rules on real-world traffic from a network tap at CU Boulder, and provide evidence that our rules have significant overlap with the GFW’s. We also find that the inferred detection algorithm would block roughly 0.6% of all connections on our network tap. Possibly to mitigate over-blocking caused by false positives, our Internet scans show that the GFW strategically only monitors 26% of connections and only to specific IP ranges of popular data centers.

We also analyze the relationship between this new form of passive censorship and the GFW’s well-known active probing system [5], which operate in parallel. We find that the active probing system also relies on this traffic analysis algorithm but has additional packet length-based rules applied. Consequently, the circumvention strategies that can evade this new blocking will also prevent the GFW from identifying and subsequently active-probing the proxy servers.

We derive various circumvention strategies from our understanding of this new censorship system. We responsibly and promptly shared our findings and circumvention suggestions with the developers of various popular anti-censorship tools, including Shadowsocks [22], V2Ray [59], Outline [42], Lantern [20], Psiphon [21], and Conjure [33]. These circumvention strategies have been widely adopted and deployed since January 2022, helping millions of users bypass this new censorship. As of February 2023, all circumvention strategies these tools adopted are reportedly still effective in China.

2 Background

2.1 Traffic Obfuscation Strategies

Tschantz et al. divide approaches to obfuscating censorship circumvention traffic into two types: steganograpic and polymorphic [57, § V]. The goal of steganographic proxies is to make circumvention traffic look like allowed traffic; the goal of polymorphism is to make circumvention traffic not look like forbidden traffic.

The two most common approaches to achieving steganography

are mimicking and tunneling. Houmansadr et

al. [39] conclude

that mimicking a protocol is fundamentally flawed and

suggest that tunneling through allowed protocols be a more censorship-resistant approach. Frolov and

Wustrow [35]

demonstrate that even when a tunneling approach is used, it

still requires effort to perfectly align protocol fingerprints

with popular implementations, in order to avoid blocking

by protocol fingerprints. For instance, in 2012, China and

Ethiopia deployed deep packet inspection to detect Tor traffic

by its uncommon ciphersuits [44, 67, 55]. Censorship

middlebox vendors have previously identified and blocked

meek [29] traffic based on

on its TLS fingerprint and SNI

value [28].

To avoid this complexity, many popular proxies opt for polymorphic designs. A common way to achieve polymorphism is to fully encrypt the traffic payload, starting from the first packet in a connection. Without any plaintext or fixed header structure to fingerprint, the censor cannot easily identify proxy traffic with regular expressions or by looking for specific patterns in traffic. This design was first introduced in Obfuscated OpenSSH in 2009 [16]. Since then, it has been employed by Obfsproxy [24], Shadowsocks [22], Outline [42], VMess [23], ScrambleSuit [68], Obfs4 [7], and partially used in Geph4 [58], Lantern [20], Psiphon3 [21], and Conjure [33].

Fully encrypted traffic is often referred to as “looks like nothing” traffic, or misunderstood as “having no characteristics”; however, a more accurate description would be “looks like random”. In fact, such traffic does have an important characteristic that sets it apart from other traffic: Fully encrypted traffic is indistinguishable from random. Since there are no identifiable headers, traffic will have high entropy homogeneously throughout the entire connection, even in the first data packet. By contrast, even encrypted protocols like TLS have relatively low-entropy handshake headers that convey supported versions and extensions.

In 2015, Wang et al. [61, §5.1] used the length and high Shannon entropy of the first packet payload in a connection to identify randomized traffic, like Obfs4. Similarly, in 2017, Zhixin Wang released a proof-of-concept tool that used the high Shannon entropy of the first three packets’ payloads in a connection to identify Shadowsocks traffic [40]. Madeye extended the tool to additionally use the payload length distribution to detect ShadowsocksR traffic [47]. He et al. [70, §IV.A] and Liang et al. [46, §II.A] used a single-bit frequency detection algorithm, rather than the Shannon entropy, to measure the randomness of Obfs4 traffic. In 2019, Alice et al. found that the GFW was using the length and entropy of the first data packet in each connection to suspect Shadowsocks traffic [5].

2.2 Active Probing Attacks and Defenses

In active probing attacks, the censor sends well-crafted payloads to a suspected server and measures how it responds. If the server responds to these probes in an identifiable way (e.g. lets the censor use it as a proxy), the censor can block it. As early as August 2011, the GFW was observed to send seemingly random payloads to foreign SSH servers that accepted SSH logins from China [49]. In 2012, the GFW first looked for a unique TLS ciphersuit to identify Tor traffic; it then sent active probes to the suspected servers to confirm its guess [67, 66, 64]. In 2015, Ensafi et al. conducted a detailed analysis of the GFW’s active probing attacks against various protocols [27]. Since May 2019, China has deployed a censorship system to detect and block Shadowsocks servers in two steps: It first uses the length and entropy of the first packet payload in each connection to passively identify possible Shadowsocks traffic, and then sends various probes, in different stages, to the suspected servers to confirm its guess [5]. In response, researchers proposed various defenses against active probing attacks, including consistent server reactions [34, 9] and application fronting [45, 36]. Shadowsocks, Outline, and V2Ray have incorporated probe-resistant designs [34, 5, 19, 43, 32, 71], making them unblocked in China since September 2020 [5], until the recent blocking in November 2021 [10].

3 Methodology

We crafted and sent various test probes between hosts inside and outside of China, letting them be observed the GFW. We observed the GFW’s reactions by capturing and comparing traffic on both endpoints. This logging allows us to identify any dropped or manipulated packets, as well as active probes.

|

Experiments

|

Time Span

|

China Vantage Points

|

US Vantage Points

|

Sections

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Characterization | Nov. 6, 2021 – May 18, 2022 (6 months) | 3 (TC, BJ),1 (Ali, BJ) | 3 (DO, SFO) | §4 |

| Re-running | Feb. 16, 2023 (1 day) | 1 (TC, BJ) | 1 (DO, SFO) | §4.1,§4.2,§4.3 |

| Active Probing | May 19 – Jun. 8, 2022 (3 weeks) | 1 (TC, BJ) | 2 (DO, SFO) | §5 |

| Internet Scan | May 12–13, 2022 (2 days) | 9 (TC, BJ) | 1 (Scan, Univ) | §6 |

| Live Traffic | Jul. – Sept., 2022 (3 months) | 1 (TC, BJ) | 1 (DO, SFO), 1 (Tap, Univ) | §7 |

Experiment timeline and Vantage points. We summarized the timeline and vantage point usage of all major experiments in Table 1. In total, we used ten VPSes in TencentCloud Beijing (AS45090) and one VPS in AlibabaCloud Beijing (AS37963). We did not observe any differences in the censoring behavior between our vantage points within China or any affected external vantage points. We used four VPSes in DigitalOcean San Francisco (AS14061): three of them were affected by the new censorship, the other one was not. We turned these four VPSes into sink servers; that is, the servers listen on all ports from 1 to 65535 to accept TCP connections, but do not send any data back to the client. We also employed two machines in the CU Boulder (AS104) for Internet scanning and live traffic analysis. We checked the IP addresses of our VPSes against IP2Location database [3], confirming their geo-locations are as reported by their providers.

Triggering censorship. Because fully encrypted traffic is indistinguishable from random data , beyond using actual circumvention tools, we developed measurement tools that send random data to trigger blocking in our study. The tools initiate a TCP handshake, send a random payload of a given length, and then close the connection.

Using residual censorship to confirm blockings. Similar to how the GFW blocks many other protocols [13, 17, 63, 14], after a connection triggers the censorship, the GFW blocks all subsequent connections having the same 3-tuple (client IP, server IP, server port) for 180 seconds. This residual censorship allows us to confirm blocking by sending follow-up connections from the same client to the same port of the server. We make five TCP connections one by one with a one-second interval in between. If all five connections failed, we conclude that the 3-tuple is blocked. Once a 3-tuple is blocked, we do not use it for further tests in the next 180 seconds.

Accouting for probabilistic blocking with repeated tests. We often had to make multiple connections with the same payload before we observed blocking. In Section 6.3, we explain that this is because the GFW employs a probabilistic blocking strategy, where censorship is only triggered approximately a quarter of the time. To account for this probabilistic behavior, we send the same payload in up to 25 connections before drawing any blocking (or not blocking) conclusion. If we can successfully make 25 connections with the same payload in a row, then we conclude that the payload (or server) is not affected by this censorship. If after sending the payload at least once, a sequence of 5 subsequent connection attempts timeout (due to residual censorship), we label the payload (and server) as affected by censorship. We use this method of repeated connections to measure blocked payloads in all the tests throughout our study.

4 Characterizing the New Censorship System

We conduct experiments to understand how the GFW detects and blocks fully encrypted connections. Detailed in Table 1, between Nov 6, 2021 and May 18, 2022, we used three VPSes in China and three sink servers in the US to conduct our experiments. During the same period, we also used one VPS in AlibabaCloud Beijing (AS37963) to repeat all our experiments. We did not observe any differences in the censoring behavior among our vantage points within China or any affected external vantage point. On February 16, 2023, we reran our experiments and confirmed all detection rules still held. This time, we used one VPS in TencentCloud BJ and one sink server in DigitalOcean SFO.

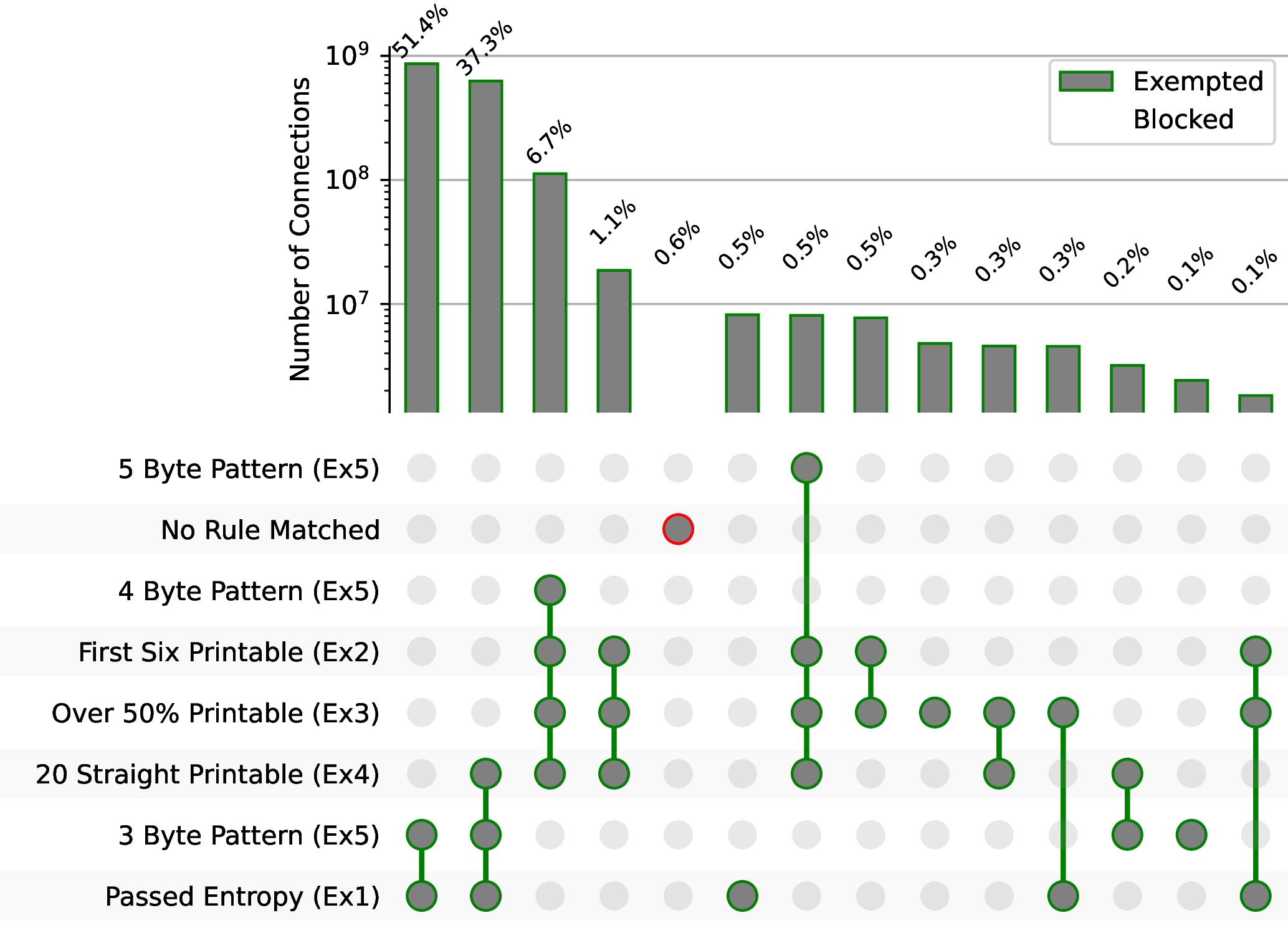

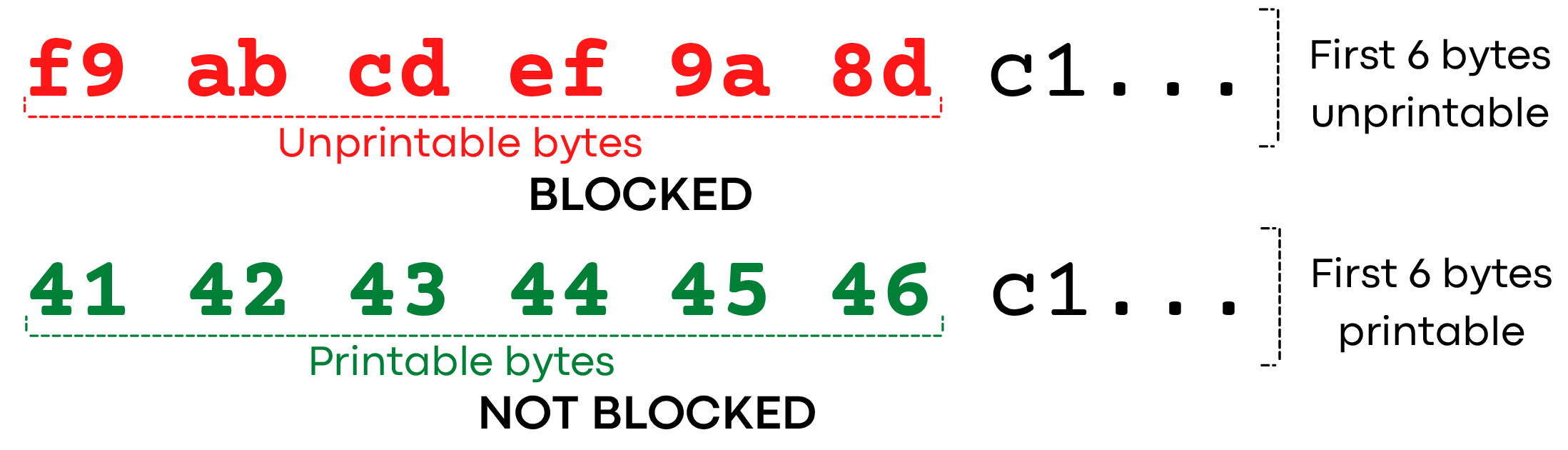

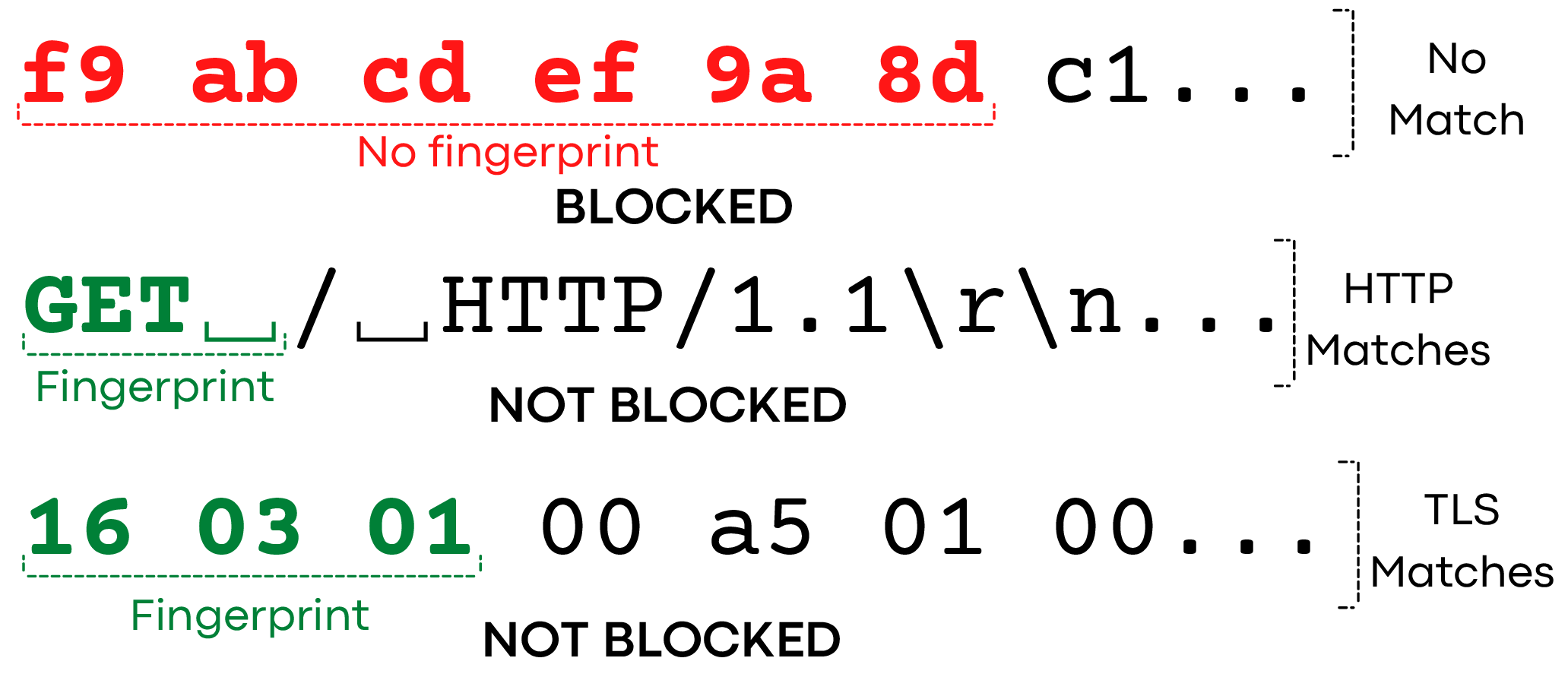

Algorithm 1 presents a high-level overview of the GFW’s detection rules we inferred, and Figure 1 illustrates examples of these inferred rules in action. While we cannot infer the order in which these rules get applied or if they are exhaustive, our experiments confirm specific components of the GFW’s censorship strategy. We find that, instead of directly defining what fully encrypted traffic is, the censor applies at least five sets crude but efficient heuristic rules to exempt traffic that is unlikely to be fully encrypted traffic; it then blocks the remaining non-exempted traffic. These exemption rules are based on common protocol fingerprints, a crude entropy test using the fraction of bits set, and the fraction, position, and maximum contiguous count of ASCII characters.

Allow a connection to continue if the first TCP payload (\(\mathtt {pkt}\)) sent by the client satisfies any of the following exemptions:

- Ex1: \(\frac {\mathit {popcount}(\mathtt {pkt})}{\mathit {len}(\mathtt {pkt})} \le 3.4\) or \(\frac {\mathit {popcount}(\mathtt {pkt})}{\mathit {len}(\mathtt {pkt})} \ge 4.6\).

- Ex2: The first six (or more) bytes of \(\mathtt {pkt}\) are \([\mathtt {0x20},\mathtt {0x7e}]\).

- Ex3: More than 50% of \(\mathtt {pkt}\)’s bytes are \([\mathtt {0x20},\mathtt {0x7e}]\).

- Ex4: More than 20 contiguous bytes of \(\mathtt {pkt}\) are \([\mathtt {0x20},\mathtt {0x7e}]\).

- Ex5: It matches the protocol fingerprint for TLS or HTTP.

Block if none of the above hold.

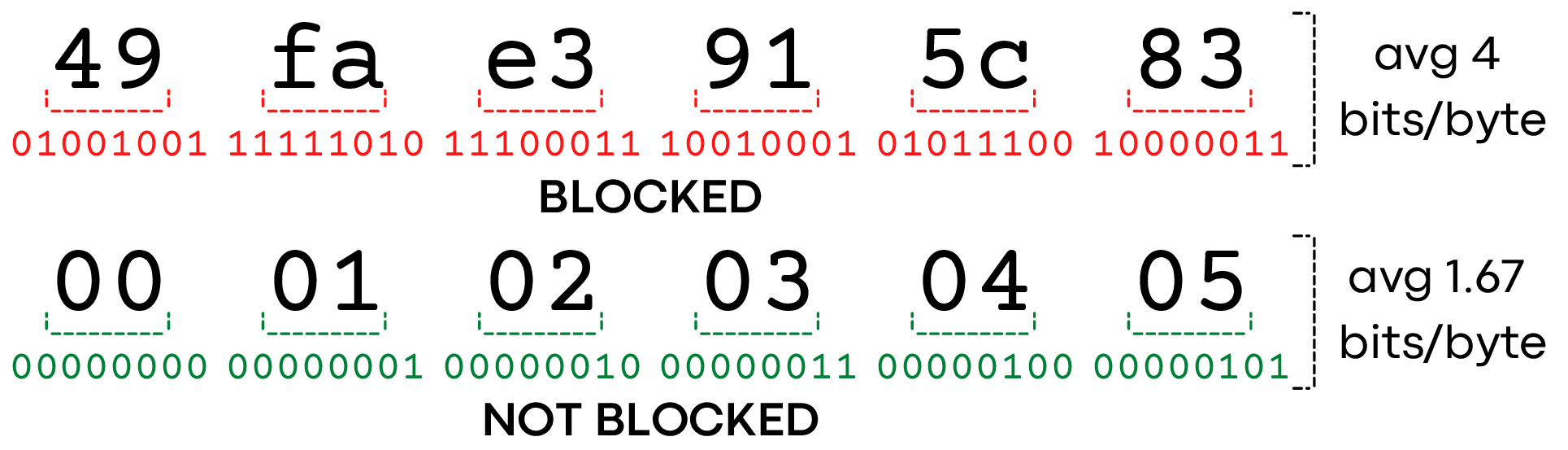

4.1 Entropy Exemption

(Ex1)

We observed that the fraction of bits set influences whether a

connection is blocked. To determine this, we sent repeated

connections to our server and observed which were blocked. In

each connection, we sent one of 256 different byte patterns,

consisting of 1 byte repeated 100 times (e.g., \x00\x00\x00..., \x01\x01\x01..., ..., \xff\xff\xff...).

We sent each pattern in

25 connections to our server, and observed if any patterns

resulted in blocking subsequent connections, indicating

the payload triggers blocking. We found 40 byte patterns triggered blocking ,

while the remaining 216 patterns did not.

Example patterns that were blocked include

\x0f\x0f\x0f..., \x17\x17\x17..., and \x1b\x1b\x1b...(and 37 others).

All of the blocked patterns consist of bytes with exactly 4 (out

of 8) bits that were \(1\) (for instance,

\x1b in binary is 00011011).

We hypothesized that the number of set bits (\(1\) bits) per byte may

play a role, as uniformly random data will have close to the

same number of total \(1\)s and \(0\)s in binary. In effect, this is

essentially measuring the entropy of the bits within the client’s

packet.

We confirmed this by sending combinations of bytes that were

individually allowed, but together resulted in being blocked. For

example, both \xfe\xfe\xfe...

and \x01\x01\x01...

were not blocked individually, but these bytes sent together as

\xfe\x01\xfe\x01... resulted in blocking.

We note \xfe\x01

has 8 (out of 16) bits set to \(1\) (an average of 4 bits per byte set),

while \xfe has 7 out of

8, and \x01 has 1 of 8

set, explaining

why individually they are allowed, but together they are

blocked.

Of course, random or encrypted data will not always have exactly half of the bits set to \(1\). We tested how close to half the GFW needed in order to block, by sending a sequence of 50 random bytes (400 bits) with an increasing number of bits set. We produced 401 bitstrings with 0–400 bits set to \(1\), and shuffled each string, yielding a set of random strings with 0–8 bits set per byte (in increments of 0.02 bits/byte). For each string, we made 25 connections and sent the string to observe if it triggered subsequent connections to be blocked. We found that all strings with \(\le 3.4\) or \(\ge 4.6\) bits/byte set were not blocked, while strings with between 3.4 and 4.6 bits/byte set were blocked.

There was a single exception to this for a string with 4.26

bits/byte set, which we determined was not blocked due to

having over 50% of its bytes be printable ASCII characters; we

show next this is an exemption rule (Ex2). We repeated our

experiment and confirmed that other strings with the same

number of bits set with less printable ASCII are indeed

blocked.

In summary, we find that the GFW exempts a connection if the fraction of bits set in the client’s first data packet deviates from half. This corresponds to a crude measure of entropy: random (encrypted) data will have close to half of the bits set to \(1\), while other protocols usually have fewer \(1\) bits per byte due to plaintext or zero-padded protocol headers. For instance, Google Chrome version 105 sends a TLS client hello with an average of only 1.56 bits set per byte, falling outside the censorship range, owing to padding with zeros.

Ex2):

the GFW exempts a connection if the first six bytes (or more) are all printable.

Ex3):

the GFW exempts a connection if its first payload has more than 50% printable ASCII.

Ex4):

the GFW counts the max number of contiguous printable bytes, and exempts a connection if the value is more than 20 bytes.

Ex1:

the GFW calculates the average number of bits set (popcount) per byte as a crude measure of entropy, and exempts a connection if the value is less than 3.4 or greater than 4.6.

Ex5):

the GFW exempts a connection if its first few bytes match HTTP or TLS protocol.

4.2 ASCII Characters

Exemption (Ex2-4)

We observed several exceptions to the bit counting rule

we discovered in Section 4.1. For instance, the pattern

\x4b\x4b\x4b... was not blocked, despite having exactly 4 bits

set per byte. Indeed, there are actually 70 characters (8 choose 4)

that have exactly 4 bits set, but our analysis found that

only 40 of those triggered censorship. What about the other

30?

These other 30 byte values all fall within the byte range that

comprises the printable ASCII characters ,

0x20–0x7e.

We conjecture that the GFW exempts characters presumably to allow

“plaintext” (human-readable) protocols.

We found three ways in which the GFW exempts connections

based on printable ASCII characters in the first packet payload

from the client: if the first six bytes are printable (Ex2); if more

than half of the bytes are printable (Ex3); or if it contains more

than 20 contiguous printable bytes (Ex4).

First six bytes are printable (Ex2). We observe that the GFW

exempts blocking if the first 6 bytes of a connection fall within

the printable byte range 0x20–0x7e. If there are

characters

outside this range in the first 6 bytes, then a connection may be

blocked, assuming it does not have other exempting properties

(for example, fewer than 3.4 bits per byte set). We tested this by

generating messages where the first \(n\) bytes were sourced from

different character sets (such as ASCII printable characters) and

the rest of the message would be random unprintable characters.

We find that for \(n < 6\), we observe censorship, but for \(n \ge 6\) where the

first \(n\) bytes are ASCII printable characters, no blocking

occurs.

Half of the first packet are printable (Ex3). If more than half

of all bytes in the first packet fall into the printable ASCII range

0x20–0x7e, the GFW exempts the connection. We tested

this by

sending packets consisting of 10 bytes of characters outside this

range (e.g. 0xe8), followed by a repeating sequence of 6 bytes: 5

within the range (e.g., 0x4b), and one outside. We repeat

this 6 byte sequence 5 times, and then pad the end of the

string with \(n\) bytes outside the range (in Python notation:

"\xe8"*10 + ("\x4b"*5 + "\xe8")*5 + "\xe8"*n).

This experiment gives us a variable-length pattern that decreases the

fraction of bytes in the printable ASCII range as we increase \(n\). We

find that for \(n < 10\), connections are not blocked, while for \(n \ge 10\) they are.

This corresponds to blocking when the fraction of printable

characters is less than or equal to half, and not blocking when

greater than half.

We design our probes to avoid triggering other GFW

exemptions, such as bit counts (Ex1), printable prefixes

(Ex2), or

runs of printable characters (Ex4). For example, we use 0x4b

and 0xe8 as our printable and non-printable characters

respectively, since they both have exactly 4 bits set. This prevents

the GFW from exempting our connection from blocking due to the bit count rule (Ex1)

discussed previously. In

addition, we avoid having contiguous runs of printable 0x4b

characters, as we observed that such runs can also exempt a

connection from blocking, which we discuss next. We repeated

our experiments with other patterns that also met these

constraints (e.g. 0x8d and 0x2e), and observed the

same

results.

More than 20 contiguous bytes are printable (Ex4). A

contiguous run of printable characters can also exempt blocking,

even if the total fraction of printable characters is less than half.

To test this, we sent a pattern of 100 bytes of a character outside

the printable range (0xe8) with a varying number of contiguous

bytes from the printable range (we used 0x4b). Our payload

started with 10 bytes of 0xe8, followed by \(n\) bytes of

0x4b,

and then \(90-n\) bytes of 0xe8, for a total length of 100 bytes.

We varied \(n\) from 0–90, and sent each of the 91 payloads

in 25 connections to our server. We found that with \(n \le 20\), the

connection was blocked. For \(n > 20\), the connection was not blocked,

indicating the presence of a run of printable characters exempts

blocking. Of course, past \(n > 50\), the connection will also be exempt,

because of Ex3.

Other encodings. We tested whether Chinese characters in the first packet were exempted from blocking in the same way as printable ASCII characters did. We used strings of 6–36 Chinese characters encoded in UTF-8, as well as GBK (identical to GB2312 for the character we used). All of these tests were blocked, suggesting that there is no exemption for Chinese characters. It is possible that the presence of Chinese characters in these encodings is rare, or that parsing these encodings adds unjustified complexity since it is hard to know where an encoded string starts or ends.

4.3 Common Protocols Exemption (Ex5)

To avoid blocking popular protocols by mistake, we observe that the GFW explicitly exempts two popular protocols. The GFW appears to infer protocols from the first 3–6 bytes of the client’s packet : If they match the bytes of a known protocol, the connection is exempted from blocking, even if the rest of the packets do not conform to the protocol. We tested six common protocols and found that the TLS and HTTP protocols are explicitly exempted. This list may not be exhaustive, as there may be other exempted protocols we did not test.

TLS. TLS connections start with a TLS Client Hello message, and the first three bytes of this message cause the GFW to exempt the connection from blocking. We observe that the GFW exempts any connection whose first three bytes match the following regular expression:

[\x16-\x17]\x03[\x00-\x09]

This corresponds to the one-byte record type, followed

by a two-byte version. We enumerated all 256 patterns of

XX\x03\x03 followed by 97 bytes of random data, and found

all patterns were blocked except those that start with either 0x16

(corresponding to the Handshake TLS record type, used in the

Client Hello) or 0x17 (corresponding to the Application Data

record type). While normal TLS connections do not begin

with Application Data [53, 52], when TLS is used over

Multipath-TCP (MPTCP) [31], it is common for one of the

TCP subflows to be used for the Client Hello and for other

subflows to send Application Data immediately after the TCP

connection is established [15]. As of today,

only TLS versions

0x03[0x00-0x03] have been defined [53, 52], but the GFW

allows even later (not yet defined) versions.

HTTP. The byte pattern used by the censor to identify HTTP

traffic is simply the method followed by a space. If a message

starts with GET␣, PUT␣,

POST␣, or HEAD␣, the connection

will be exempt from blocking. The space character (0x20)

after each verb is necessary to exempt connections from

blocking. Not including this space character, or replacing it with

any other byte will not exempt the connection. The other

HTTP methods (OPTIONS␣, DELETE␣, CONNECT␣, TRACE␣,

PATCH␣) fall into the ASCII printable exemption (Ex2),

as the first 6 bytes are printable characters. We find that

the method is case-insensitive: GeT␣, get␣, and

similar

variations are exempt. Typos in the verb (e.g., TEG␣) are not

exempt.

Non-exempted protocols. We tested other common protocols:

SSH, SMTP, and FTP would be exempt as they all start with at

least 6 bytes of printable ASCII (rule Ex2). DNS-over-TCP is

exempt due to containing a large fraction of zeros, making it

exempt by the Ex1 rule. However, if a large enough amount of

random data was appended after a DNS-over-TCP message, it

would be blocked.

This observation raises the question of why the censor has

explicit rules to exempt TLS and HTTP, but not other protocols.

After all, the censor does not need to exempt these two protcols

explicitly: HTTP will commonly be exempt by printable

ASCII for the first 6 bytes (rule Ex2), and TLS Client Hello

messages have relatively low bit-wise entropy (rule Ex1),

owing to many zero fields. Nonetheless, the censor may

employ these simple but efficient rules to quickly exempt the

bulk of traffic (TLS and HTTP) from the more in-depth

analysis of calculating the popcount, fraction of ASCII,

etc.

4.4 How the GFW Disrupts Connections

Once the GFW detects fully encrypted traffic using Algorithm 1, it blocks the subsequent traffic as introduced below.

Packets are dropped from client to server. We triggered the GFW’s blocking and compared the captured packets from both the sending client and receiving server. We observe that after triggering blocking, the client’s packets are dropped by the GFW, and do not reach the server. However, packets sent by the server are not blocked and are still received at the client.

UDP traffic is not affected. The new censorship system is limited to TCP. Sending a UDP datagram with a random payload cannot trigger the blocking. Additionally, once a 3-tuple (client IP, server IP, server Port) is blocked due to a triggering TCP connection, UDP datagrams to or from the same (server IP, server Port) are not affected. Because of the absence of UDP blocking, users may experience odd behavior while using Shadowsocks: they can still access websites or use apps that rely on UDP (e.g. QUIC or FaceTime), but cannot access websites that use TCP. This is because Shadowsocks proxies TCP traffic with TCP and proxies UDP traffic with UDP. Not detecting or blocking UDP traffic may reflect the censor’s worse is better engineering mindset. From a practical view, the current TCP blocking can already effectively paralyze these popular circumvention tools, while employing UDP censorship requires additional resources and invites extra complexity to the censorship system.

Traffic on all ports can get blocked. We set up a sink server listening on all ports from 1 to 65535 in US. We then let our client in China continuously make connections with 50-byte random payloads to each port of the US server and stop when a port got blocked. We find that blocking can happen on all ports from 1 to 65535. Therefore, running circumvention servers on an unusual port cannot mitigate the blocking. We also do not observe any difference in censor’s behaviors among ports.

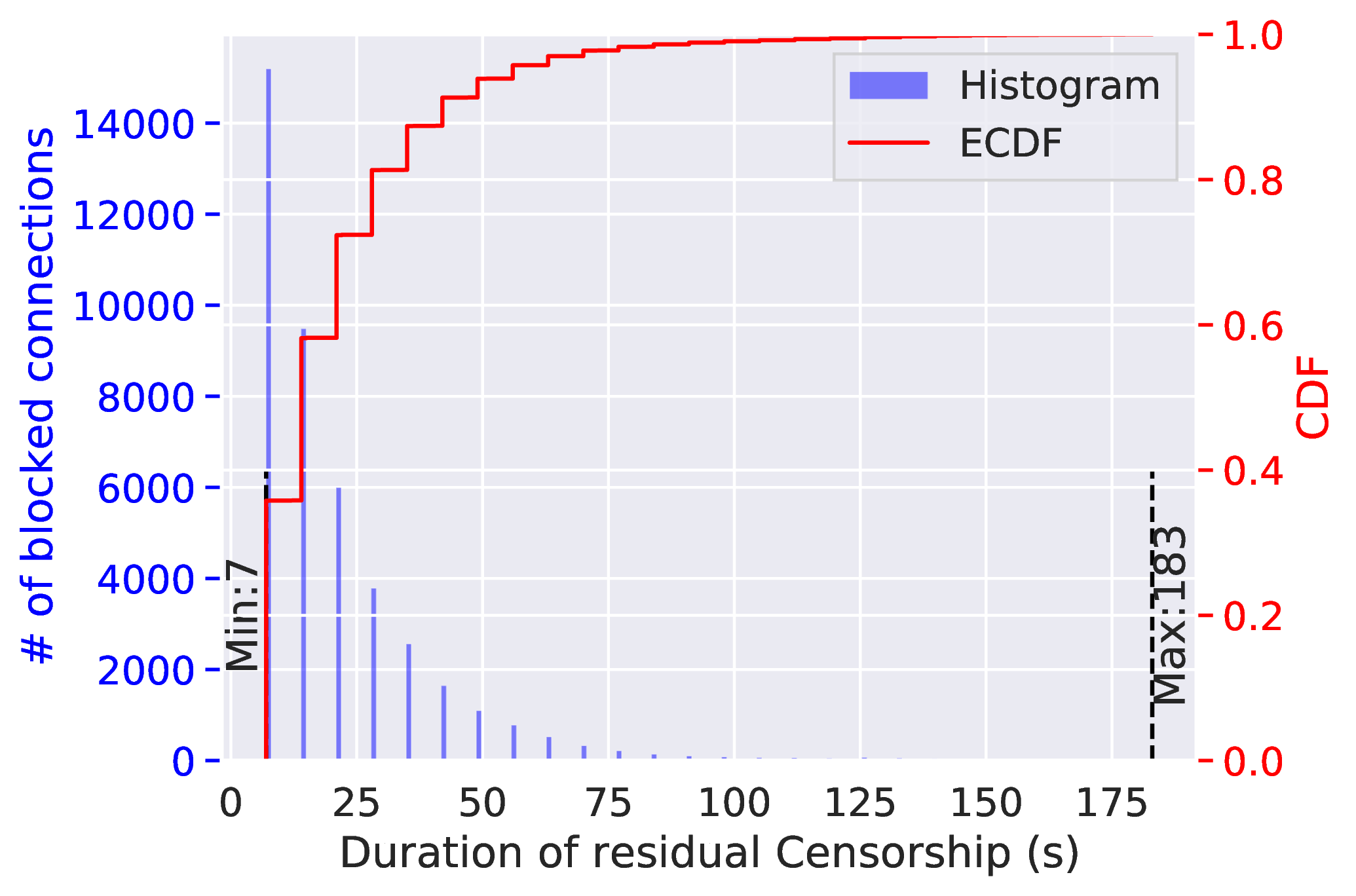

The duration of residual censorship is affected by the number of on-going residual blocking. We find that once this new censorship system blocks a connection, it continues to drop all subsequent TCP packets having the same 3-tuple (client IP, server IP, server port) for 120 or 180 seconds. This behavior is often referred to as “residual censorship” [13, 17, 63, 14]. Unlike some other residual censorship systems [13], the GFW’s residual censorship timer does not reset when additional packets are sent.

We also find that the GFW seems to limit the number of connections it residually blocks at any given time. We let our clients in China repetitively make connections to 500 ports of a single server simultaneously. In each connection, the client sent 50 bytes of random data and then closed the connection. We recorded the duration of each occurrence of residual censorship. As shown in Figure 2, in comparison to the 180 s duration when only one port is blocked, the residual censorship duration in this experiment decreased dramatically.

4.5 How the GFW Reassembles Flows

In this section, we examine how the GFW’s new censorship system reassembles flows and considers flow directions.

A complete TCP handshake is necessary. We observe

that sending a SYN packet followed by a PSH+ACK packet

containing random data (without the server completing its end of

the handshake) is not sufficient to trigger blocking. The

blocking is thus harder to exploit for residual censorship

attacks [13].

Only client-to-server packets can trigger the blocking. We

find that the GFW not only checks if the random data is sent to a

destination IP address that falls in an affected IP range, it also

examines and will only block if the random data is sent from

client to server. The server here is defined as the host that sends a

SYN+ACK during the TCP handshake.

We learned this by setting up four experiments between the same two hosts. In the first experiment, we let the Chinese client connect and send random data to the foreign server; in the second experiment, we still let the Chinese client connect to the foreign server, but let the foreign server send random data to client; in the third experiment, we let the US client connect and send random data to Chinese server; in the forth experiment, we let the US client connect to the Chinese server, but then let the Chinese server send random data to the US client. Only connections in the first experiments were blocked.

The GFW only examines the first data packets. The GFW

appears to only analyze the first data packet in a TCP connection,

without reassembling the flows with multiple data packets. We tested this with the following experiment.

After a TCP

handshake, we send the first data packet with only one byte of

payload \x21. After waiting for one second, we

then send the

second data packet with a 200-byte random payload. We repeated

the experiment 25 times, but the connections never got blocked.

This is because after seeing the first data packet, the GFW had

already exempted the connections by rule Ex1 as it contained

100% printable ASCII in the payload. In other words, if

the GFW reassembled multiple packets into a flow during

its traffic analysis, it would have been able to block these

connections.

We found that the GFW does not wait until seeing an

ACK response from the server to block a connection. We

configured our server to drop any outgoing ACK packets

with an iptables rule. We then made connections with

200-byte random payloads to the server. The GFW still blocked

these connections though the server never sent any ACK

packets.

The GFW waits more than 5 minutes for the first data packets. We examine how long the GFW monitors a TCP connection after the TCP handshake, but before it sees the first data packet. From the observation that it requires a complete TCP handshake to trigger the blocking, we infer the GFW may be stateful. It is thus reasonable to suspect the GFW only monitors a connection for a limited amount of time, as it can be expensive to maintain a state forever without expiring it.

Our client completed TCP handshakes and then waited

for 100, 180, or 300 seconds, before sending 200 bytes of

random data. We then repeated the experiment but used

iptables rules to drop any RST or TCP keepalive packets in

case they helped the GFW keep the connection state active.

We found that these connections still triggered blocking,

suggesting the GFW maintained connection states for at least five

minutes.

5 Relation with the Active Probing System

|

Crafted Payload

|

Affected Server

|

Unaffected Server

|

||

|

# connections

|

# probes

|

# connections

|

# probes

|

|

| 2-byte random (\xfe\x01) | 33k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| 50-byte random | 29k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| 200-byte random | 33k | 141 | 169k | 679 |

| "GET " + 50-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| \x16\x03\x03 + 50-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| \x17\x03\x03 + 50-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| "GET " + 50-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| \x16\x03\x03 + 200-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| \x17\x03\x03 + 200-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| Low bit counting (2.5) | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| High bit counting (5.2) | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| More than half printable | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| First six bytes printable + 200-byte random | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

| More than 20 contiguous bytes | 170k | 0 | 169k | 0 |

As introduced in Section 2.2, the GFW has been sending active probes to Shadowsocks servers since 2019 [5]. In this section, we study the relationship between this newly discovered real-time blocking system and the existing active probing system. By conducting designed measurement experiments and analyzing historical datasets, we show that while these two censorship systems work in parallel, the current traffic analysis module of the active probing system applies all five sets of exemption rules summarized in Algorithm 1 and Figure 1, with one additional rule that examines the payload length of the first data packet. We also show evidence that the traffic analysis algorithm used by the active probing system [5] may have evolved since 2019.

Active probing experiment. Prior to the deployment of this new real-time blocking system, inferring the traffic analysis algorithm of the active probing system was extremely challenging, if possible at all. This is because the GFW employs an arbitrary delay between seeing a triggering connection and sending active probes [5, §3.5], making it difficult to account for which probes by the GFW are triggered by which connections we send. Now that we have inferred a list of traffic detection rules of this new blocking system in Section 4, we can test if a payload exempted by Algorithm 1 will also not get suspected by the active probing system.

We conducted the experiments between May 19, 2022 and June 8, 2022. As shown in Table 2, we crafted 14 different types of payloads: three of them are random data with lengths of 2, 50, and 200 bytes; the remaining 11 were data with various lengths that will only be exempted by exactly one of the exemption rules in Algorithm 1. We then sent the same 14 payloads from a VPS in Tencent Cloud Beijing China, to 14 ports of two different hosts in DigitalOcean San Francisco US. One US host is known to be affected by the current blocking system, while the other US host is unaffected. This way, if we received any probes from the GFW, we know certain exemption rules used by the current blocking system are not used by the active probing system.

In total, our client in China sent around 170k connections to each port of the two US servers. We then took steps to isolate the GFW’s probes from other Internet scanners’. We check the source IP address of each probe against IP2Location database [3] and AbuseIPDB [2]. We do not consider it as a probe from the GFW if it was a non-Chinese IP or from a known spammer IP address. We further check if the probe belongs to any known types of probes sent by the GFW.

The two systems work independently. The new censorship machine makes its blocking decisions purely based on passive traffic analysis, without relying on China’s well-known active probing infrastructure [67, 5, 66, 64, 27]. We know this because, while the GFW still sends active probes to the servers, in more than 99% of the tests, the GFW did not send any active probes to the server before blocking a connection. For example, as summarized in Table 2, we made 33,119 connections but only received 179 active probes. Indeed, similar to the findings by prior work [5, §4.2], active probes are rarely triggered.

We want to emphasize that this finding does not mean that defenses against active probing are not necessary or not important anymore [34, 5, 9]. On the contrary, we believe that the GFW’s reliance on purely passive traffic analysis is partially because Shadowsocks, Outline, VMess, and many other censorship circumvention implementations have adopted effective defenses against active probing [34, 5, 9, 19, 43, 32, 71]. The fact that the GFW still sends active probes to servers implies that the censor still attempts to use active probing to accurately identify circumvention servers whenever possible.

The active probing system applies the five exemption rules, with one additional length rule, to suspect traffic. This experiment suggests two points. First, similar to the findings by Alice et al. [5, §4.2], the active probing system applies an additional rule to examine the length of the connection. In our case, only connections with 200-byte payloads ever triggered the active probing, not ones with 2 bytes or 50 bytes. Second, the traffic exempted by any of the five rules discovered in Algorithm 1 will also not trigger the active probing system.

The active probing system has evolved since 2019. We want

to know if the same detection rules in Algorithm 1 were historically

used to trigger active probing. To analyze it, we obtained

282 payloads that got replayed (and thus once triggered

the GFW) in the low-entropy experiment from Alice et

al. [5, §4.1]. We then wrote a program to determine if

a

payload would be exempted by the current blocking system, and

fed the program with the obtained 282 payloads. As a result,

45 probes that previously triggered active probing were

exempted (by rule Ex3). On May 19, 2022, we repeatedly sent

these 45 payloads through the GFW, confirming that they

were indeed exempted from the current blocking. For each

payload, we made 25 connections with it from a VPS in

TencentCloud Beijing to a sink server in DigitalOcean SFO.

This result suggests that the GFW has likely updated the

traffic analysis module of its active probing system since

2020. In addition, the probes sent by the current GFW are

also different from those observed in 2020 [5, §3.2].

The new probes are essentially random payloads that are

distributed in trios of 16, 64, and 256 bytes. For each of these

lengths, the GFW sent about the same number of probes:

48, 46, and 47 to one server, and 238, 228, and 233 to the

other.

6 Understanding the Blocking Strategies

In this section, we conduct measurement experiments to characterize the censor’s blocking strategies. We find that, possibly to mitigate false positives and reduce operation costs, the censor strategically limits the scope of blocking to specific IP ranges of popular data centers, and it applies a probabilistic blocking strategy to 26% of all connections to these IP ranges.

6.1 Internet Scanning Experiment

On May 12, 2022, we performed a 10% IPv4 Internet scan on TCP port 80, from a server located at CU Boulder. Following prior work that identifies unreliable hosts in Internet scans [41], we remove IPs that respond with a TCP window of 0 (as we cannot send them data), or do not accept a subsequent connection. This leaves us with 7 million scannable IPs. We then randomly and equally split these 7 million IP addresses into nine subsets, and assigned each to our nine vantage points in TencenCloud Beijing datacenter. We then used a measurement program we wrote and installed in all nine vantage points for the experiment. For each IP, the program connects to its port 80 sequentially up to 25 times, with a one-second interval in between. In each connection, we send the same 50 bytes of random data that can trigger the blocking. If we see 5 consecutive connections time out (fail to connect) after we have sent data, we label the IP as affected. Otherwise, if all 25 connections succeed, we label the IP as unaffected. We label IPs that we cannot connect to at all as unknown (e.g., the server is down, or a network failure unrelated to the GFW prevents us from connecting in the first place).

We also repeated this process but sent 50 bytes of \x00, which

does not trigger blocking by the GFW. If a server is marked as

affected in this test, it is likely due to the server blocking us, and

not the GFW, and we remove these IPs from our results. This

leaves just over 6 million IPs.

Finally, we remove “ambiguous” results that may be due to intermittent network failures or unreliable vantage points. Specifically, we remove IPs that either of our random or zero scans labelled unknown (we were never able to connect), or had intermittent connection timeouts (e.g., several connections timed out, but not 5 consecutively). This leaves 5.5 million IPs that we can easily label as unaffected (all 25 connections succeeded) or affected (at some point it appeared blocked after we sent random data).

6.2 Not All Subnets/ASes are Affected Equally

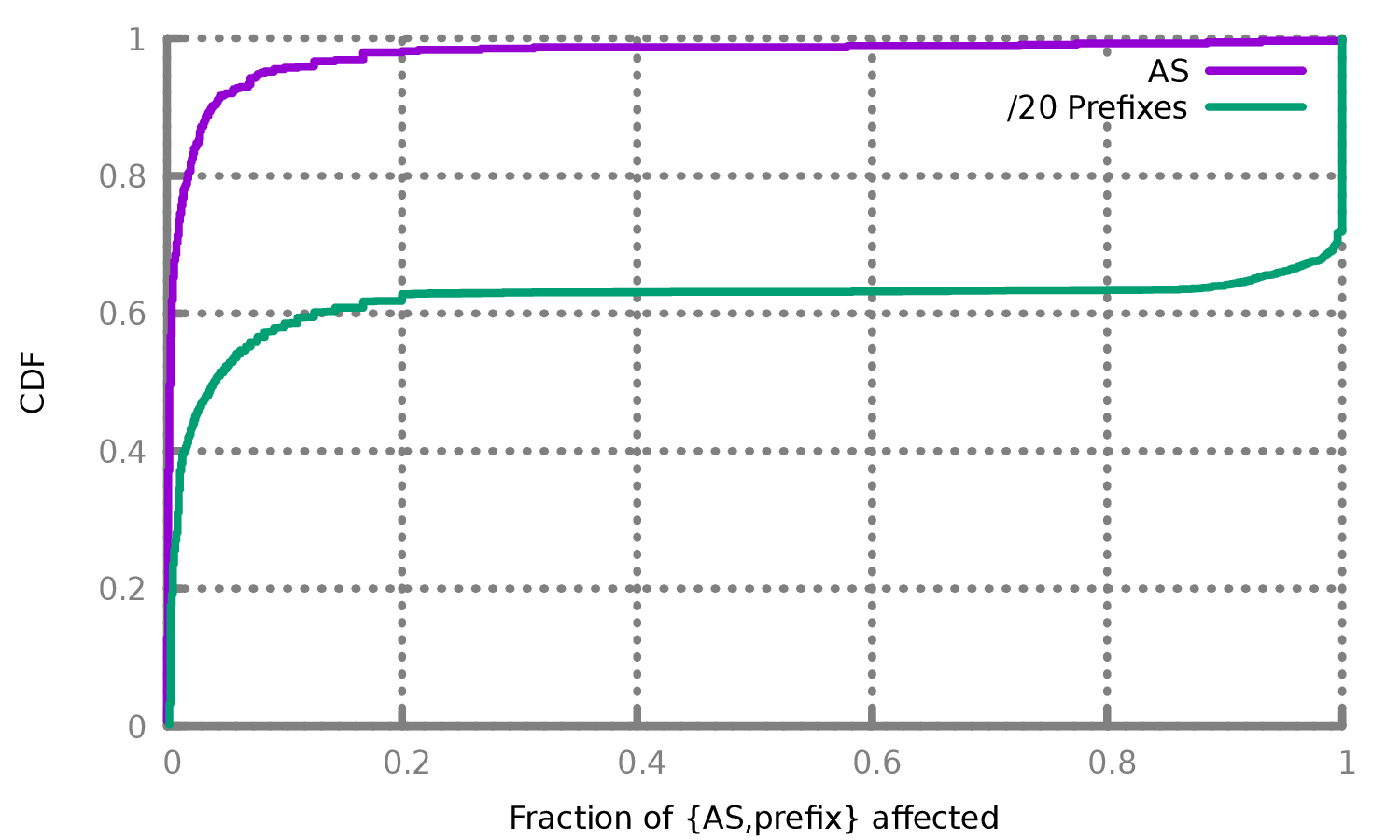

Of the 5.5 million processed IPs, 98% of them are unaffected by the GFW’s blocking, suggesting that China is fairly conservative in employing this new censorship. We group these 5.5 million IP addresses into their allocated IP prefixes and ASes, using pyasn with an AS database from April 2022 [51]. For IP prefixes larger than /20, we break the allocation into a set of /20 prefixes to keep allocations roughly the same size. Our 5.5 million IPs comprise 538 unique ASes that have at least 5 results, and the vast majority of these are largely unaffected by the GFW’s blocking.

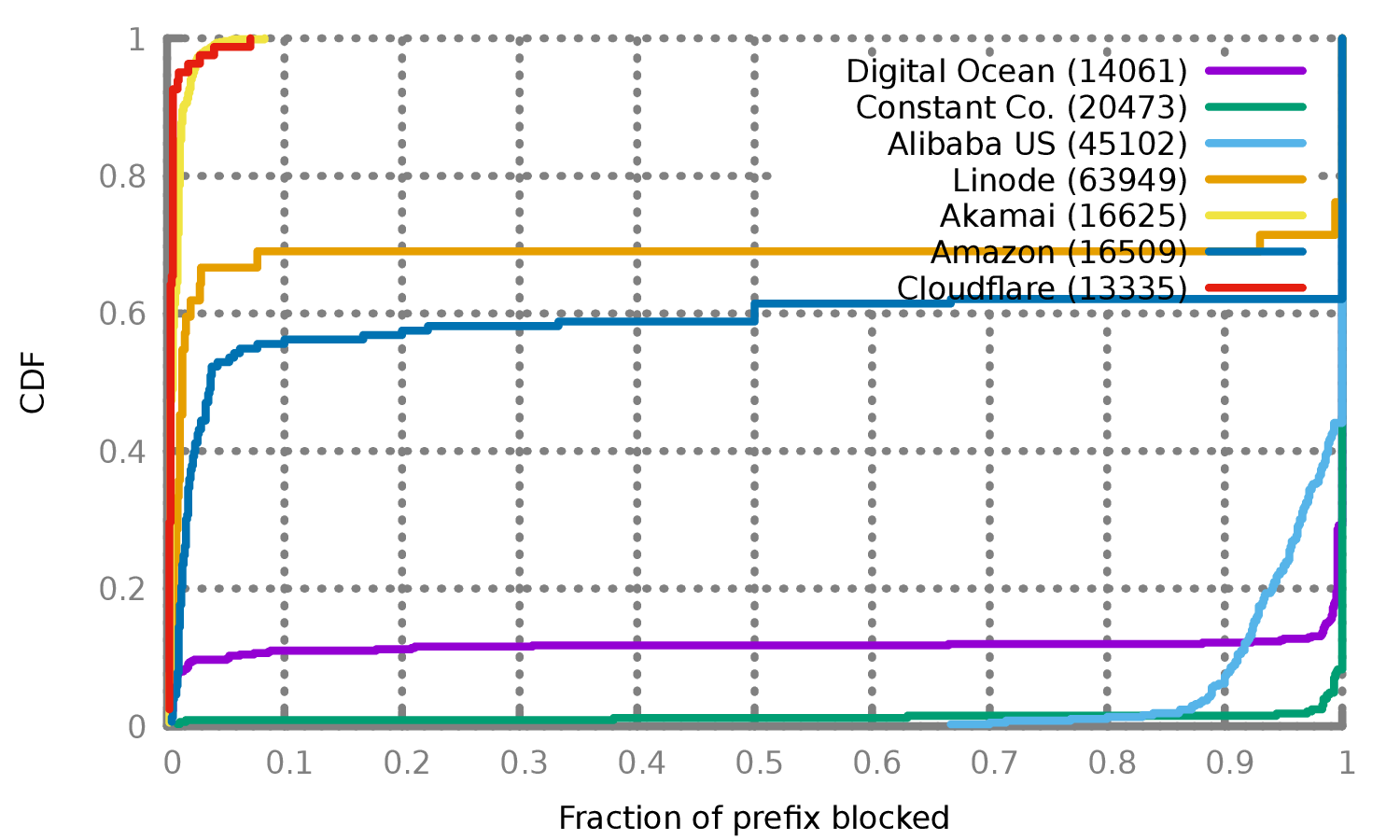

Figure 3 shows the distributions of the fraction of affected ASes and /20 prefixes. We found that more than 90% ASes are affected in an all-or-nothing way: either all IP addresses we tested in the AS are affected by the GFW’s blocking, or no IP addresses we tested in the AS are unaffected. We also observe that only a few ASes are affected: over 95% of ASes see less than 10% of their IPs affected, and only 7 ASes see more than 30% of their IPs affected.

Figure 4 shows the top affected ASes. While this is skewed toward larger ASes (which have more IPs in our scan), it shows both ASes that are heavily affected (e.g., Alibaba US, Constant) and ones that are not (Akamai, Cloudflare). In addition, some ASes have a mix of affected and not affected prefixes (Amazon, Digital Ocean, Linode). All of the affected or partly-affected ASes we see are popular VPS providers that could be used to host proxy servers, while large unaffected ASes do not typically sell VPS hosting to individual customers (e.g. CDNs).

6.3 Characterizing Probabilistic Blocking

As introduced in Section 3, we send up to 25 connections with the same payload before drawing any conclusions about blocking. This is necessary because the censor implements blocking probabilistically. In other words, just sending a random payload to an affected server once would only sometimes trigger blocking; however, if one keeps making connections with the same payload to the affected server, blocking will occur eventually. This raises the question on what the probability is for a connection to get blocked, and why the censor implements blocking only probabilistically.

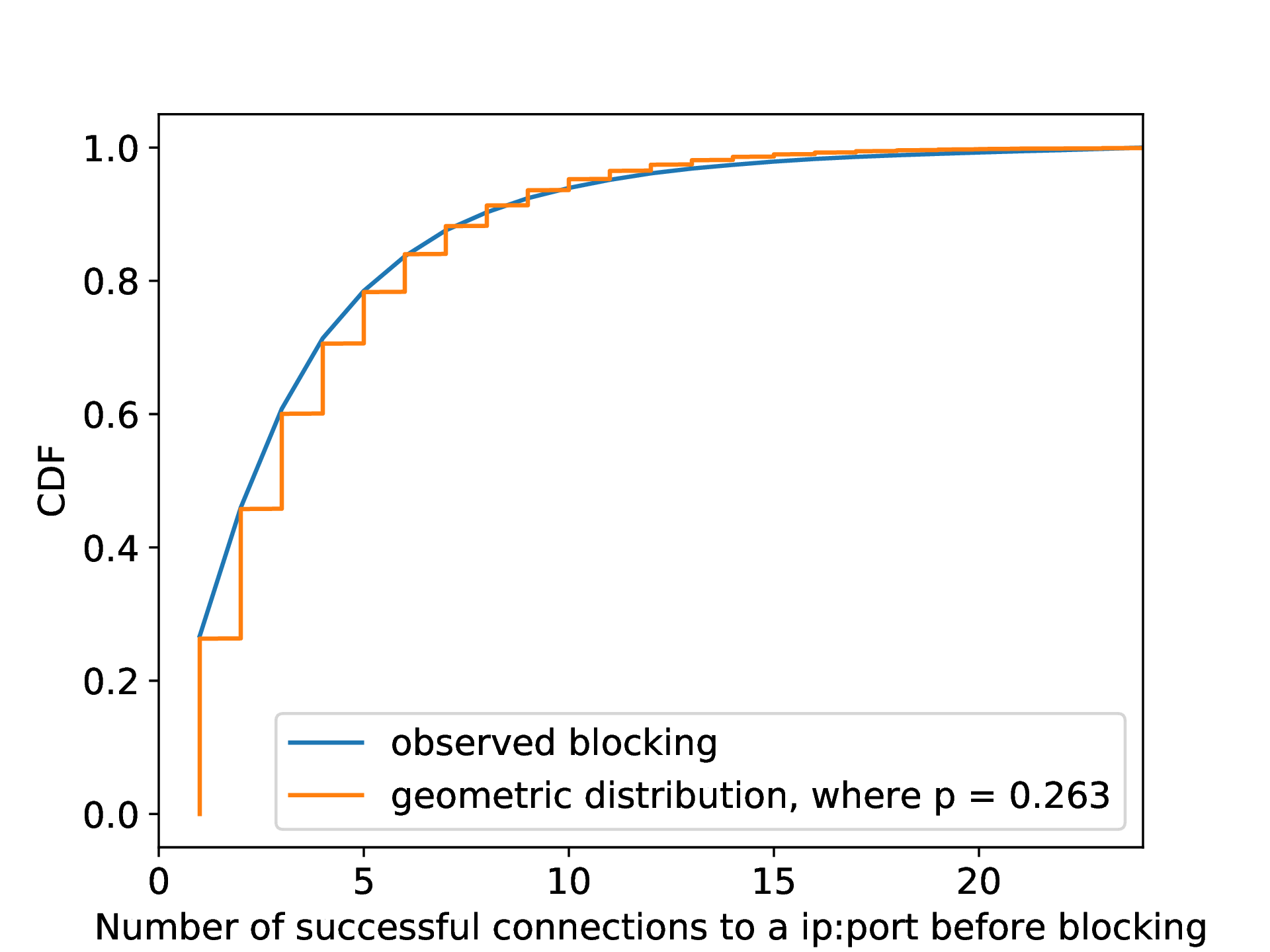

Estimating the blocking rate. From our 10% Internet scan (Section 6.2), there were 109,489 IP addresses that we label as blocked. As shown in Section 5, the distribution of the number of successful random data connections we can make to each IP address before getting blocked fits a geometric distribution. This result suggests that the blocking of each connection is independent, with a probability of \(26.3\%\).

Why probabilistic blocking is used. We conjecture that the censor employs probabilistic blocking possibly for two reasons: First, it allows the censor to only examine one-fourth of connections, reducing computation resources. Second, it helps the censor reduce the collateral damage to non-circumvention connections. While this reduction also comes at the expense of lower true positives, the residual censorship may make up for it: once a connection is determined to be blocked, subsequent connections are also blocked for several minutes after, making it difficult for proxy users to successfully connect once detected. This may also further support prior claims that censors put more emphasis on reducing their false positive rate than in achieving a high true positive rate [57].

7 Evaluating the GFW’s Detection Rules

In this section, we evaluate the false positive rate and comprehensiveness of the GFW’s detection rules we inferred in Section 4. To determine the impact this blocking may have on regular traffic, we simulate the inferred detection rules to traffic on our university network without actually blocking any traffic. Different from the GFW, we simulate the detection rules against all TCP connections observed without limiting the detection to 26% of connections to specific IP ranges of popular data centers. We expect to see little to no circumvention traffic in this network, and any traffic that would be blocked under detection rules likely represents false positive blocking. We find that the inferred detection algorithm would block roughly 0.6% of all connections on our network. Due to the black-box nature of the GFW, our inferred rules may only be a subset of what the GFW uses; however, we show that all connections that Algorithm 1 would block were indeed blocked when we sent their prefixes along with random data through the GFW, suggesting our inferred rules have good coverage of what the GFW uses.

7.1 Traffic Analysis Experiment

We have access to a 40 Gbps network tap at CU Boulder that allows us to process copies of all incoming and outgoing packets on our campus. Using this, we collected a dataset comprising only destination port numbers and the first 6 bytes of payload data for connections that do not already satisfy the other exemption rules in Algorithm 1. More precisely, we implemented a custom packet analysis tool using PF_RING [50]. For each connection, we inspected the first data packet sent by the client. We ensured that the packet has a correct TCP checksum, and that its sequence number is the first expected data packet after the TCP handshake in the connection (making sure we have not missed the first data packet). For connections that are not exempted by Algorithm 1—i.e., those we expect to be blocked—we logged the destination port and the first six bytes of the connection to help identify its protocol.

We performed this collection between July 2022 and September 2022. In total, we analyzed 1.7 billion connections and logged 442,928 unique 6-byte prefixes of would-be-blocked connections. For each of these 442,928 6-byte prefixes, we append the same 194-byte random data to it to make a 200-byte payload. We then repetitively sent each payload past the real GFW in September 2022, to test whether they were indeed blocked, or if instead there were exemptions we had not previously identified. For each payload, we made up to 25 connections with it from a VPS in TencentCloud Beijing to a sink server in DigitalOcean SFO.

7.2 Experiment Results and Analysis

Estimating the false positive rate. In total, we analyzed 1.7 billion connections on our network between July 2022 and September 2022. For each connection, we determine which rules in Algorithm 1 would exempt it from being blocked. As shown in Figure 6, we observe on average that 0.6% of TCP connections from our tap would be blocked under the GFW’s detection rules we inferred.

There are at least two strategies the censor employs to reduce the false positive rate. First, as introduced in Section 6, the GFW only applies this censorship to a fraction of IP subnets. This decision may be an attempt to mitigate the base-rate problem faced by the censor [11]. Since relatively few connections in total are proxy connections, even a small false positive rate (such as 0.6%) would result in blocking mostly benign traffic, if applied broadly. By narrowing the scope of IPs it is applied to, China can reduce the collateral damage of its censorship. Second, as explored in Section 6.3, even for traffic towards this subset of IP subnets, the GFW is observed to block only about one-quarter of all traffic, reducing the false positive rate to one-fourth.

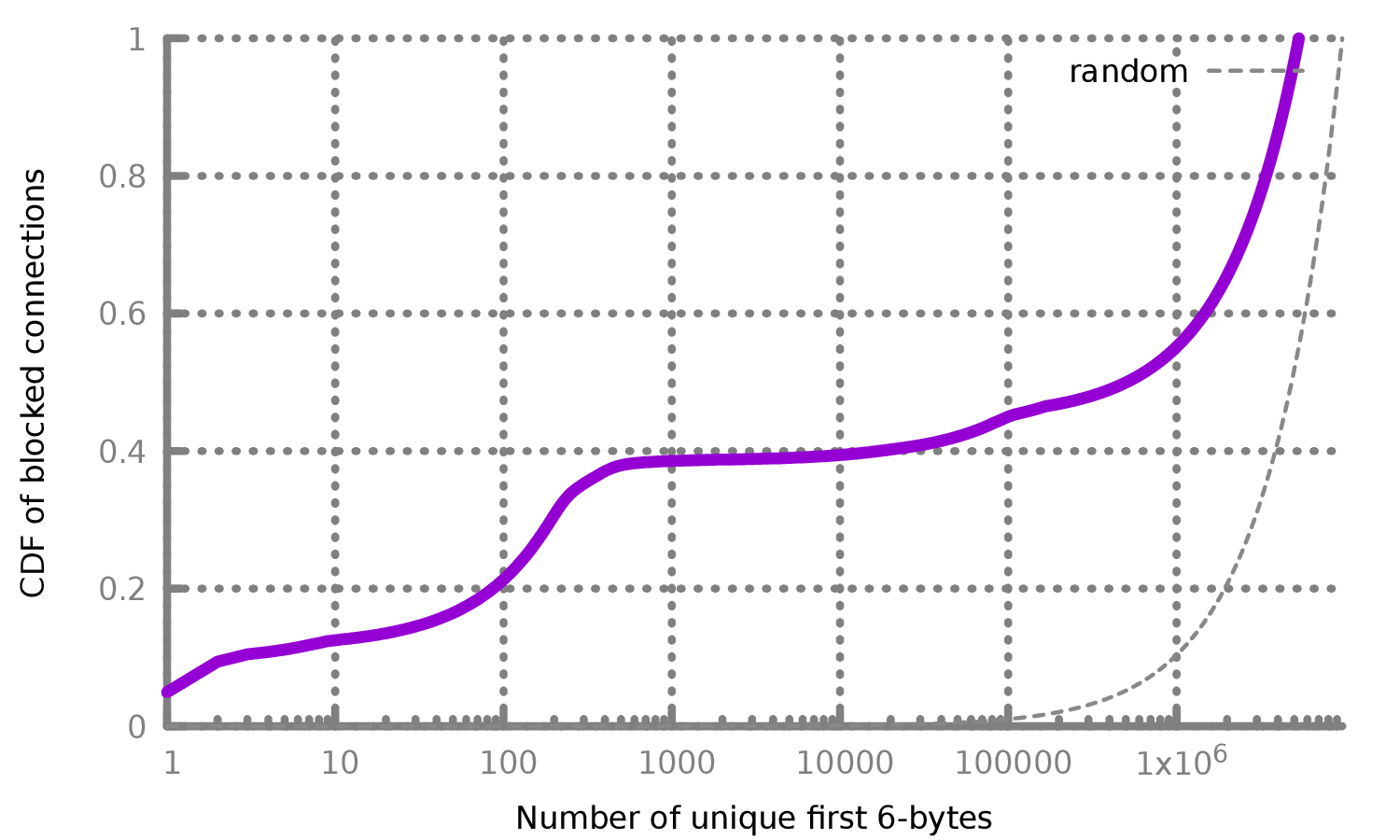

It is possible that the 0.6% of connections we identified may be fully encrypted proxies. To investigate this possibility, we keep a count of the number of unique 6-byte prefixes we see in each connection that would be blocked under the GFW’s rules. If these connections are all truly fully encrypted proxies, we would expect to see a uniform distribution over the \(256^6\) possible 6-byte values. Otherwise, if there are 6-byte values that occur frequently, it could be headers of popular protocols, indicating false positives in the GFW’s blocking.

Figure 7 shows the distribution of the first 6 bytes of all 9.7 million connections from our tap that would be blocked under the GFW rules we inferred. In addition, Table 3 shows the top 6-byte values from would-be blocked connections. While we are not able to identify many of these protocols, their frequency along with the low entropy indicates that they are not likely to be fully encrypted proxies.

|

Bytes in hex

|

Port

|

Occurences

|

|

| 45 44 00 01 00 00 | 5222 | 479K | 5.0% |

| ee 2f 8c ec 40 d1 | 8000 | 427K | 4.4% |

| 00 00 00 00 00 00 | 50386 | 104K | 1.1% |

| 00 c4 71 58 64 51 | 443 | 34K | 0.4% |

| 00 c4 71 42 30 6e | 443 | 33K | 0.3% |

| 0e 53 77 61 72 6d | 7680 | 32K | 0.3% |

| 1b 00 04 c6 27 53 | 8886 | 32K | 0.3% |

| c6 e6 cd ed 00 00 | 33445 | 29K | 0.3% |

| 00 01 00 00 0f 00 | 443 | 27K | 0.3% |

| 16 f1 04 00 a1 00 | 80 | 12K | 0.1% |

Estimating the comprehensiveness of the inferred rules.

Among the 442,928 payloads we crafted and sent past the real

GFW, we found only one prefix got exempted by the GFW,

which alerted us to the TLS Application Data prefix exemption

(\x17\x03[\x00-\x09]). We added this exemption to our

inferred rules (Ex5). This result suggests our inferred rules have

good coverage of what the GFW uses.

8 Circumvention Strategies

Our understanding of this new censorship system allows us to derive multiple circumvention strategies. In Section 8.1 and Section 8.2, we introduce two widely adopted countermeasures that have been helping users in China bypass censorship since January 2022 and October 2022, respectively. We discuss other circumvention strategies in Section A. We responsibly and promptly shared our findings and suggestions with the developers of various popular anti-censorship tools that have millions of users, which we detail in Section 8.3.

8.1 Customizable Payload Prefixes

The exemption rules Ex2 and

Ex5 from Algorithm 1 only look at

the first several bytes in a connection, allowing the GFW to

efficiently exempt non-fully encrypted traffic; however, this lends

itself to a potential countermeasure. Specifically, we propose

prepending a customizable prefix to the payload of the first

packet in a (circumvention) connection.

Customizable IV header. Shadowsocks connections begin with

an Initialization Vector (IV), which is of length 16 or 32 bytes

depending on the encryption ciphers [22]. As

introduced in

Section 4.2, turning the first six (or more) bytes of the IVs into

printable ASCII will exempt connections by the rule Ex2.

Similarly, turning the first three, four, or five bytes of the IVs

into common protocol headers will exempt connections

by the rule Ex5 (e.g., turning the first three bytes of an IV

into 0x16 0x03 0x03). These countermeasures require

minimal changes to the client and no changes to the server, and

therefore has been adopted by many popular circumvention

tools [72, 62, 48, 56]. Restricting the first few

bytes of a

32-byte IV to be printable ASCII will not reduce the randomness

to the point that affects the security of encryption. For example,

even fixing the first six bytes to printable ASCII still leaves the

IVs with 26 random bytes, which is still more than a typical

16-byte IV.

Limitations. This is a stopgap solution and could potentially be blocked by the censor fairly easily. The censor may skip the first several bytes and apply the detection rules to the rest data in a connection. Protocol mimicry is also difficult in practice [39]. The censor can enforce stricter detection rules, or actively probe a server to check if it is genuinely running TLS or HTTP. Nevertheless, the fact that this strategy still works as of February 2023, more than one year since its adoption by many popular circumvention tools in January 2022, underscores that even simple solutions can be effective against finite-resourced censors [8, 57, 30].

8.2 Altering Popcount

As introduced in Section 4.1, the GFW exempts a connection

if

its first data packet has an average popcount-per-byte \(\le 3.4\) or \(\ge 4.6\)

(Ex1).

Based on this observation, one can increase (decrease) the

popcount by inserting additional ones (zeroes) into the packet to

bypass censorship. We introduce and analyze a flexible scheme

that alters the popcount-per-byte to any given value or range. We

implemented this scheme on Shadowsocks-rust [54]

and

Shadowsocks-android [6], helping users in

China bypass

censorship since October 2022 [8]. In January 2023,

a

large-scale circumvention service in China (that asked not to be

named), also implemented a version of this scheme and found

similar success.

At a high level, we take original fully-encrypted packets as input: By operating only on the ciphertexts, we do not risk violating confidentiality. When sending a packet, we first compute its average popcount-per-byte; if the value is greater than 4, then we determine how many one-bits we would have to add to the packet in order to obtain a popcount over 4.6. Conversely, if the popcount is less than 4, then we determine how many zero-bits we would have to add to decrease the popcount to less than 3.4. In either case, we append the necessary number of one- or zero-bits to the original ciphertext and then append 4 bytes denoting the number of bits added, ultimately giving us a bit-string \(B\) that has a popcount-per-byte that would not subject it to censorship.

Of course, simply appending ones or zeroes would be easy to fingerprint. To address this, we do bit-level random shuffling. In particular, we leverage the existing shared secrets, such as password, as a seed to deterministically construct a permutation vector. In each connection, we update this permutation vector and use it to shuffle all the bits in the bit-string \(B\) before sending it. To decode, the receiver first updates the permutation vector and then uses it to un-shuffle the bit-string; then it reads the last 4 bytes to determine the number of bits added, removes that number of bits, and is thus able to recover the original (fully encrypted) packet.

In practice, we take two additional steps to further obfuscate the traffic. Since it is an obvious fingerprint if all connections share the same popcount-per-byte value, we set the goal value to a parameterizable range. Second, since the 4-byte length tag in plaintext may be a fingerprint, we encrypt it (the same way these circumvention tools encrypt proxy traffic).

This scheme has several advantages. First , the scheme supports parameterizable popcount-per-byte in case the GFW updates its popcount rule to block an even larger range. Second , because of its careful design, there are no obvious fingerprints that would signal to the censor that this is a popcount-adjusted packet. Finally , it incurs low overhead; it adds only as many ones (or zeroes) strictly necessary (padded to the nearest byte). In the worst case—increasing the popcount from 4 to 4.6—this incurs only about 17.6% overhead. As a result, it could feasibly be applied not just to the first packet, but to every packet in the connection, thereby insulating it against future updates to the censor that might look past the first packet.

8.3 Responsible Disclosure

On November 16, 2021, ten days after the GFW employed this new blocking [10], we revealed details of this new blocking to the public [37, 38]. With the development of our understanding of this new blocking, we derived and evaluated different circumvention strategies. We responsibly and promptly shared our findings and suggestions with the developers of various popular anti-censorship tools that have millions of users , including Shadowsocks [22], V2Ray [59], Outline [42], Lantern [20], Psiphon [21], and Conjure [33]. Below we introduce our disclosure and the responses from the anti-censorship community in detail.

On January 13, 2022, we shared our first circumvention strategy with a group of developers. This solution, detailed in Section 8.1, requires minimal code changes to the clients and no changes to the servers. By January 14, 2022, Shadowsocks-rust developer zonyitoo, V2Ray developer Xiaokang Wang and Sagernet developer nekohasekai had already added this circumvention solution as an option to their clients [72, 62, 48]. On October 4, 2022, database64128 implemented a user-customizable version of this strategy on Shadowsocks-go [18]. On October 25, 2022, Outline developers adopted a highly customizable solution for their client [56]. On October 14, 2022, we released a modified Shadowsocks [8] that employed the popcount-altering strategy we detailed in Section 8.2.

As of February 14, 2023, all circumvention strategies adopted by these tools are reportedly still effective in China. In January 2023, Outline developers reported that the number of Outline servers (that opted-in for anonymous metrics) had doubled since they adopted the mitigation above. In January 2023, a large circumvention service provider in China (that asked not to be named at this time) also implemented our proposed scheme and has also found success.

While we did not study countries other than China, our proposed circumvention strategies are reported to be also working in Iran, another country that reportedly blocks and throttles fully encrypted proxies [65]. On February 13, 2023, Lantern developers reported that the adopted protocol “accounted for the majority of our Iran traffic” since January 2023. On February 13, 2023, a different circumvention service provider reported that, after enabling Outline’s mitigation feature in November 2022, their services turned from being completely blocked to serving 850k daily users from Iran.

9 Ethics

Censorship measurement research carries an element of risk and responsibility which we take seriously. Our research involves handling sensitive network traffic, scanning large numbers of hosts, and performing network measurements in a sensitive country. Due to the sensitive nature of this work, we approached our institution’s IRB with our detailed research plan for review. While the IRB determined that the work does not involve human subjects (and thus does not require IRB review), we have designed and implemented extensive precautionary efforts to minimize potential risks and harms. In this section, we discuss these risks and detail the precautionary measures we adopted to manage and mitigate them.

Traffic analysis. We worked closely with our university’s network operators, who have extensive experience in managing such projects, to deploy our network measurement tool to ensure it is within the network use policy and respects user privacy. We design our experiments to avoid collecting potentially sensitive information, such as IP addresses, which could reveal human identifiable information. We collect minimal information and focus on tracking aggregate statistics to avoid potentially identifying individuals. Specifically, we only analyzed the very first TCP data packet in each connection and ignored any subsequent packets. In addition, we only logged the first six bytes of data and keep an aggregate count of their occurrences; no raw traffic was ever inspected by a human nor logged. We practiced the least privilege principle, giving only a subset of our team access to this data.

Internet scanning. To minimize the risk of overwhelming servers when performing Internet-wide scans, we followed the best practices outlined in prior work in Internet scanning and widescale censorship measurement [26, 60]. We set up a dedicated webpage, along with a reverse DNS to it, on port 80 of our scanning host at CU Boulder. The webpage explains what data our scanning collects, and offers ways to opt out of future scans. During our entire experiment period, we received and honored seven removal requests, which is typical based on past experiences scanning the Internet [25, §5.3] [26, §5.1]. Our follow-up scans to these servers were low-bandwidth: we sent less than 100 bytes for each request, and each server only performed one connection at a time to avoid overwhelming their network or connection pool resources.

The use of vantage points. Active censorship measurement from within censored countries requires additional considerations and prudent evaluation. We first explored the possibility of performing the measurement remotely but confirmed that this censorship could not be triggered from outside of China. While it may be low risk to have sensitive queries observed by the censor, we follow similar standards discussed in prior work to limit the number of these sensitive queries we send [5]. In particular, we only send queries on port 80 to servers that are listening on that port, and made no concurrent connections to the same server to avoid overwhelming server operations.

Our research team consulted experts with a deep understanding of the nature and legal concerns of Chinese censorship, who helped us make informed decisions on which VPS providers to use and how to use them. We selected two large-scale VPS providers run by well-known commercial companies in order to avoid any potential legal risks to individuals. We registered our VPSes with the accurate identity and contact information of one of our researchers who is neither a citizen of nor resides in China. We received no complaints from the providers throughout our research. As done in prior work [5], we do not inform these large VPS providers of the experiments ahead of time, to avoid potential experiment bias (e.g. interference in results) or placing potential legal obligations or burdens on the VPS providers.

We manage the risk of potentially getting any server blocked by the GFW temporarily or in the long term. For all hosts we controlled in this study, we assigned dedicated IP addresses to them to avoid blocking shared IP addresses. In addition, we rented our non-censoring network hosts from a VPS provider that permits censorship circumvention usage and even offers automatic installation of circumvention tools. Similar to the findings in prior work on residual censorship in China [13, 17, 63, 14], we tested using our own servers and confirmed that the GFW never blocked any of our machines’ IP addresses for more than 180 seconds, and the blocking only affected traffic from our clients to the servers, without interfering with traffic from others’. Knowing that our servers were used for five months but never experienced any long-term blocking, we proceeded to perform our large-scale scans.

10 Conclusion

In this work, we exposed and studied China’s latest censorship system that dynamically blocks fully encrypted traffic in real time. This powerful new form of censorship has affected many mainstream circumvention tools partially or in full, including Shadowsocks, Outline, VMess, Obfs4, Lantern, Phiphon, and Conjure. We conducted extensive measurements to infer various properties about the GFW’s traffic analysis algorithm and evaluated its comprehensiveness and false positives against real-world traffic. We use our knowledge of this new censorship system to derive effective circumvention strategies. We responsibly disclosed our findings and suggestions to the developers of different anti-censorship tools, helping millions of users successfully evade this new form of blocking.

Acknowledgments

We thank our shepherd and other anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and feedback. We also thank the brave users in China for immediately reporting the blocking incidents to us. We are grateful to Benjamin M. Schwartz, zonyitoo, nekohasekai, database64128, AkinoKaede, Max Lv, Mygod, DuckSoft, and many other developers from the anti-censorship community for their prompt patches, assistance, and discussions. We express our sincere appreciation to Outline developer, Vinicius Fortuna, at Jigsaw for offering insightful suggestions and assisting us in reaching out to the community. We thank Lantern developers Adam Fisk and Ox Cart for sharing the deployment experience of their tool in Iran. We also thank Milad Nasr for his informative input. We appreciate klzgrad sharing thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of the paper. We are also deeply grateful to David Fifield for providing a proof-of-concept patch against obfs4, contributing to the discussions, providing constructive feedback and suggestions on an earlier draft of the paper, and offering guidance and support throughout the entire study.

This work was supported in part by NSF grants CNS-1943240, CNS-1953786, CNS-1954063 and CNS-2145783, by the Young Faculty Award program of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under the grant DARPA-RA-21-03-09-YFA9-FP-003, and by DARPA under Agreement No. HR00112190125. The views, opinions, and/or findings expressed are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

Availablity

To maintain reproducibility and encourage future research, we released our source code and data: https://gfw.report/publications/usenixsecurity23/en.

References

- 19th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/19th_Central_Committee_of_the_Chinese_Communist_Party .

- Abuseipdb. https://www.abuseipdb.com/ .

- Ip2location lite data. http://www.ip2location.com/ .

- Sixth Plenary Session of the 19th CPC Central Committee. https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-cn/中国共产党第十九届中央委员会第六次全体会议 .

- Alice, Bob, Carol, Jan Beznazwy, and Amir Houmansadr. How China detects and blocks Shadowsocks. In Internet Measurement Conference . ACM, 2020. https://censorbib.nymity.ch/pdf/Alice2020a.pdf .

- Shadowsocks android developers. Shadowsocks-android. https://github.com/shadowsocks/shadowsocks-android .

- Yawning Angel et al. Obfs4 specification. https://gitlab.com/yawning/obfs4/blob/master/doc/obfs4-spec.txt .

- Anonymous and Amonymous. Sharing a modified Shadowsocks as well as our thoughts on the cat-and-mouse game, October 2022. https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues/136 .

- Anonymous, Anonymous, Anonymous, David Fifield, and Amir Houmansadr. A practical guide to defend against the GFW’s latest active probing, January 2021. https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues/58 .

- Anonymous, Vinicius Fortuna, David Fifield, Xiaokang Wang, Mygod, moranno, et al. Properly configured shadowsocks servers reportedly blocked in china, November 2021. https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues/69#issuecomment-962666385 .

- Stefan Axelsson. The base-rate fallacy and its implications for the difficulty of intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security , pages 1–7, 1999. https://www.cse.psu.edu/~trj1/cse543-f16/docs/Axelsson.pdf .

- Kevin Bock. Iran: A new model for censorship, March 2020. https://geneva.cs.umd.edu/posts/iran-whitelister/ .

- Kevin Bock, Pranav Bharadwaj, Jasraj Singh, and Dave Levin. Your censor is my censor: Weaponizing censorship infrastructure for availability attacks. In Workshop on Offensive Technologies . IEEE, 2021. http://www.cs.umd.edu/~dml/papers/weaponizing_woot21.pdf .

- Kevin Bock, iyouport, Anonymous, Louis-Henri Merino, David Fifield, Amir Houmansadr, and Dave Levin. Exposing and circumventing China’s censorship of ESNI, August 2020. https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues/43#issuecomment-673322409 .

- Olivier Bonaventure. MPTLS : Making TLS and Multipath TCP stronger together. Internet-Draft draft-bonaventure-mptcp-tls-00, Internet Engineering Task Force, October 2014. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-bonaventure-mptcp-tls/00/ .

- brl. Obfuscated OpenSSH. https://github.com/brl/obfuscated-openssh .

- Zimo Chai, Amirhossein Ghafari, and Amir Houmansadr. On the importance of encrypted-SNI (ESNI) to censorship circumvention. In Free and Open Communications on the Internet . USENIX, 2019. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/foci19-paper_chai_update.pdf .

- database64128. taint: add unsafe stream prefix, October 2022. https://github.com/shadowsocks/shadowsocks-org/issues/204#issuecomment-1266710067 .

- database64128, zonyitoo, Xiaokang Wang, and nekohasekai. Shadowsocks 2022 Edition: Secure L4 Tunnel with Symmetric Encryption, October 2022. https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues/58 .

- Lantern developers. Lantern. https://github.com/getlantern .

- Psiphon3 developers. Psiphon3. https://psiphon.ca/ .

- Shadowsocks developers. Shadowsocks aead cihpher specification. https://shadowsocks.org/guide/aead.html .

- VMess developers. Vmess. https://www.v2fly.org/en_US/developer/protocols/vmess.html .

- Roger Dingledine. Obfsproxy: the next step in the censorship arms race. https://blog.torproject.org/obfsproxy-next-step-censorship-arms-race , February 2012.

- Zakir Durumeric, Michael Bailey, and J. Alex Halderman. An Internet-Wide view of Internet-Wide scanning. In 23rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 14) , pages 65–78, San Diego, CA, August 2014. USENIX Association. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity14/technical-sessions/presentation/durumeric .

- Zakir Durumeric, Eric Wustrow, and J. Alex Halderman. ZMap: Fast internet-wide scanning and its security applications. In 22nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 13) , pages 605–620, Washington, D.C., August 2013. USENIX Association. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity13/technical-sessions/paper/durumeric .

- Roya Ensafi, David Fifield, Philipp Winter, Nick Feamster, Nicholas Weaver, and Vern Paxson. Examining how the Great Firewall discovers hidden circumvention servers. In Internet Measurement Conference . ACM, 2015. http://conferences2.sigcomm.org/imc/2015/papers/p445.pdf .

- David Fifield. Cyberoam firewall blocks meek by TLS signature. https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/traffic-obf/BpFSCVgi5rs/ , 2016.

- David Fifield, Chang Lan, Rod Hynes, Percy Wegmann, and Vern Paxson. Blocking-resistant communication through domain fronting. Privacy Enhancing Technologies , 2015(2), 2015. https://www.icir.org/vern/papers/meek-PETS-2015.pdf .

- David Fifield and Lynn Tsai. Censors’ delay in blocking circumvention proxies. In Free and Open Communications on the Internet . USENIX, 2016. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/foci16/foci16-paper-fifield.pdf .

- A. Ford, C. Raiciu, M. Handley, O. Bonaventure, and C. Paasch. TCP Extensions for Multipath Operation with Multiple Addresses. RFC 8684, RFC Editor, March 2020. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8684 .

- Vinicius Fortuna. Outline changes since the prelinimary report, August 2020. https://github.com/net4people/bbs/issues/22#issuecomment-670781627 .

- Sergey Frolov, Jack Wampler, Sze Chuen Tan, J. Alex Halderman, Nikita Borisov, and Eric Wustrow. Conjure: Summoning proxies from unused address space. In Computer and Communications Security . ACM, 2019. https://jhalderm.com/pub/papers/conjure-ccs19.pdf .

- Sergey Frolov, Jack Wampler, and Eric Wustrow. Detecting probe-resistant proxies. In Network and Distributed System Security . The Internet Society, 2020. https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/23087.pdf .

- Sergey Frolov and Eric Wustrow. The use of TLS in censorship circumvention. In Network and Distributed System Security . The Internet Society, 2019. https://tlsfingerprint.io/static/frolov2019.pdf .

- Sergey Frolov and Eric Wustrow. HTTPT: A probe-resistant proxy. In Free and Open Communications on the Internet . USENIX, 2020. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/foci20-paper-frolov.pdf .

- GFW Report. The GFW has now been able to dynamically block any seemingly random traffic in real time, November 2021. https://twitter.com/gfw_report/status/1460796633571069955 .

- GFW Report. 有证据表明中国的防火长城已经对任何看似随机的流量进行动态的封锁, November 2021. https://twitter.com/gfw_report/status/1460800856086003717 .

- Amir Houmansadr, Chad Brubaker, and Vitaly Shmatikov. The parrot is dead: Observing unobservable network communications. In Symposium on Security & Privacy . IEEE, 2013. https://people.cs.umass.edu/~amir/papers/parrot.pdf .

- isofew. sssniff, 2017. https://github.com/isofew/sssniff .

- Liz Izhikevich, Renata Teixeira, and Zakir Durumeric. \(\{\)LZR\(\}\): Identifying unexpected internet services. In 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21) , pages 3111–3128, 2021. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity21/presentation/izhikevich .

- Jigsaw. Outline. https://getoutline.org/ .

- Jigsaw. Outline v1.1.0. https://github.com/Jigsaw-Code/outline-ss-server/releases/tag/v1.1.0 .

- George Kadianakis. GFW probes based on tor’s ssl cipher list, 2011. https://gitlab.torproject.org/legacy/trac/-/issues/4744 .

- klzgrad. NaïveProxy. https://github.com/klzgrad/naiveproxy .

- Di Liang and Yongzhong He. Obfs4 traffic identification based on multiple-feature fusion. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS) , pages 323–327, 2020. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9202018 .

- madeye. sssniff, 2017. https://github.com/madeye/sssniff .